The CoachSafely Blog: When your son is not always safe at second

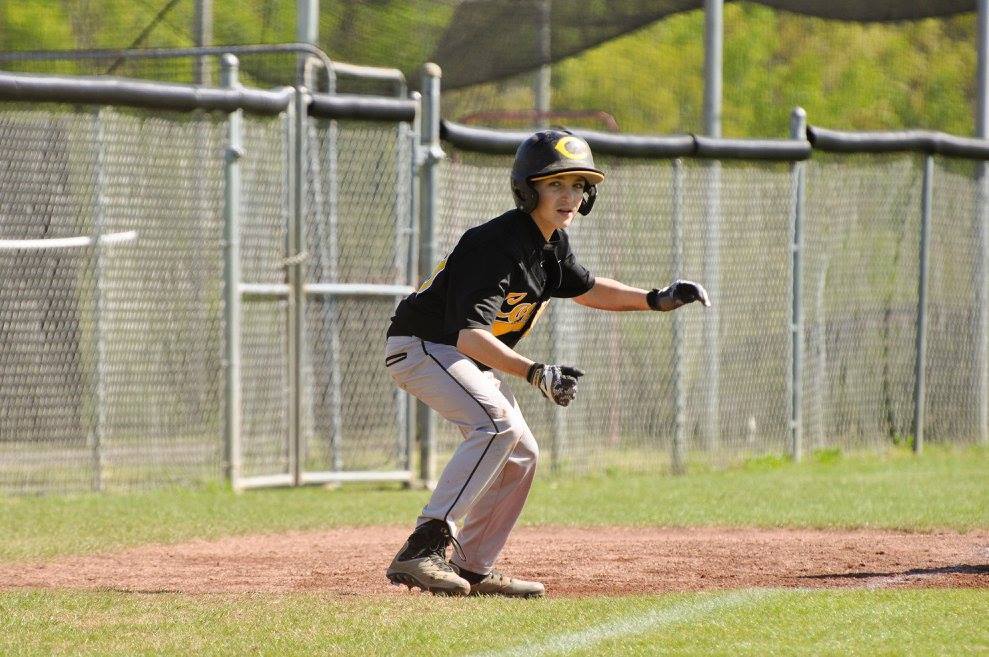

The kid known as “Rabbit” went into second base the way he liked, launching himself head first, believing it was the quickest way to the bag. The shortstop flashed in front to field the catcher’s throw, and boom, there was contact, hard enough to pop Rabbit’s helmet from his head.

But OK. He was safe. Or so we thought.

He got up, brushed himself off and took his lead but advanced no farther. As the inning ended, he returned to the bench to grab his glove. I was sitting in the stands keeping score when the head coach came hurrying out of the dugout in my direction.

“You need to come check on Kaiser,” he said. “He doesn’t look good.”

No, he didn’t. My 13-year-old son was terribly pale. He said his head hurt because the shortstop’s knee had struck him in the forehead underneath his batting helmet. He said he felt like he might have to throw up.

There was a reason. He had a concussion, which we discovered a few days later after taking him to a doctor. He didn’t play the rest of that game. He wouldn’t play or even practice again for more than a month, on his baseball or basketball travel teams, and he would miss plenty of school in the last month of the academic year with persistent headaches. Nothing will teach you as a parent to take concussions as brain injuries seriously like having your bouncy, bubbly 13-year-old son – who would practice dunking by jumping off a folding table in the driveway while still in his baseball uniform – confined to a dark, quiet room for what seems like an eternity.

Fortunately, his coaches put Kaiser’s health ahead of his value to the team. He received excellent care as he went through the return-to-learn and return-to-play protocols of the Concussion Clinic at Children’s of Alabama. Everyone followed the playbook on how to take a concussion seriously and handle it properly.

But what if? What if his middle school coaches weren’t trained as required by the Alabama High School Athletics Association? What if I hadn’t taken the concussion test required by our community park as a youth coach there? What if I didn’t personally know former Alabama and NFL fullback Kevin Turner, who had just lost his terrible battle with ALS after a career littered with concussions?

What if Kaiser had gone back in that game after taking that knee to the forehead and taken a fastball to the helmet? It happens. Injuries happen every day in youth sports, in practices and games, so often that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has labeled youth sports injuries as an epidemic. The good news: The CDC also says that fully half of those injuries are preventable.

The state of Alabama understands. We became a national leader in keeping our kids active, healthy and safe when the State Legislature passed the Coach Safely Law in 2018. It’s the first law in the nation that requires all youth coaches of kids 14 and under in Alabama to complete a comprehensive training course in injury recognition and prevention annually.

It makes perfect sense. Think about it. You wouldn’t drop off your 6-year-old son or 10-year-old daughter at a pool without a lifeguard. Yet every day we drop our kids off at youth baseball, softball, basketball, football or soccer practice without necessarily knowing if their mostly volunteer coaches are educated on how to keep them safe.

Now we as youth coaches can have that knowledge we need through the CoachSafely course and we as parents can have that peace of mind we want. At the next practice, it’s up to us as parents to ask our children’s coaches one very important question:

Do you Coach Safely?

____________________________________________________________

Kevin Scarbinsky is Director of Communications for the CoachSafely Foundation. Write him at kscarbinsky@coachsafely.org.